Doris Dufresne 1926-2016

The oblivion we come from ends, and our lives begin, with our earliest memory. My life began when I was two years, two months, and two weeks old on the day that my newborn sister was carried home to our apartment—the apartment with the leaky roof, the ice box, the console radio, and the walk-through closet to the Vanderhoofs’ living room, at 16 Security Road, in the Lincolnwood public housing project—began when I had my first nightmare, and in the morning, my first conversation.

I woke up crying because in the night, and despite my vigilance, a band of shadowmen crossed the kitchen along the green walls, past the table and behind the stove and slipped through the crack in the closed door to the baby’s room. I screamed, but none of the inattentive adults in the living room heard me, and then the worst thing that could happen did happen. I told Mom that Paula had been stolen by the shadowmen. She assured me that she would never let anything bad happen to her babies. She told me I’d had a dream, that’s all, and explained what a dream was, but I found her explanation preposterous: how can we see things that aren’t really there? She showed me a comic book on the coffee table—Lefty borrowed them from Uncle Richard—and pointed out the source of my evil two-dimensional shadowmen there on the illustrated page. I kept crying; she lifted me onto her lap, rocked me, and rubbed my back. She offered to take me to see the living, sleeping baby, but I didn’t want the backrub to end.

We all wanted to be alone with Mommy. She was most herself in solitude or when she was with one of her children. Cyndi remembers a long ride to Old Orchard Beach sitting in Mom’s lap, her head on Mom’s chest, feeling the vibration of Mom’s voice as she spoke with Dad and being comforted as she might once have been in the womb. She remembers mornings when she was four, drinking coffee with Mom at the kitchen table, the two of them chatting about the long day in front of them, Mom would iron and watch her stories, Cyndi would color outside the lines, chatting, sipping, and waiting for the Cushman Bread man to arrive with his treasure of coffee cake. Paula remembers Mom showing up at school and walking into the classroom with Paula’s forgotten lunch, and at that moment and for the first time, Paula realized how beautiful her mother was. Mark loved lounging with Mom on the couch in the den watching Boston Movietime. State Line potato chips and Polar cola were involved.

Doris had simple needs: enough money to pay the bills, to buy us back-to-school clothes at the Mart and groceries at the Big D, and maybe a little extra for a long weekend at the beach. She wanted to be happy, but she had a complicated relationship with happiness. She yearned for it, but she didn’t trust it. Too much well-being tempted fate and summoned trouble. She was a realist, not a romantic; a pessimist at times, but never a cynic. And she did know how to have fun despite her caution and those intimations of her mortality.

She liked bingo, candlepin bowling, and shopping, especially pock-a-book shopping. She led the hora dance at every wedding, often with her son-in-law Denis, the guy she once told Paula to dump—he’s too much like your father. She threw legendary Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve parties. Everyone she and Lefty knew was invited and all of them showed up. Some Christmas mornings we had to step around senseless and snoring survivors to get to the gifts. She could get silly as on a recent girls’ night out in Wilmington with Cyndi, when, after shopping and a doctor’s visit, the two of them had a pillow fight in the hotel room, and Doris laughed till she peed her pants. Or at her coronation as Miss America in the living room with the terrifying orange and brown Spanish furniture at 177 Warner Ave, she in her two-piece brown bathing suit, golden sash, and plastic tiara, a makeshift scepter, posing for photos as Mark sang, “Here she comes . . .”

In her salad days, Dot could drink like a Jesuit. When she did, she saved her drink stirrers at the bar so she’d know when she’d had enough. Are nine gin and tonics enough? Are they ever enough? She relied on routines like the drink stirrers to give her a sense of control, I think. She was determined to face life on her own terms. When she finally quit smoking, she kept a carton of Pall Malls in the freezer. Now she had the choice. To smoke or not to smoke. No one was going to tell her to quit. She would decide.

Some of her decisions in this regard seemed perverse and baffling. She had a long secretarial career at Lawrence McCoy Lumber Merchants but refused full-time employment with benefits and paid vacations. I guess you could say she was stubborn. She chose to work there all those years as a temp for Manpower. She said in that way she could call in sick any day she wanted to. She might need to get some tanning in before the weekend, for instance. It was her habit to lie in the sun on a chaise longue in our blighted backyard from early April till Labor Day, and by late May, she was nut brown. She slathered her body in baby oil laced with iodine. She never got skin cancer. She lived till 90 without a wrinkle.

I would call her parenting style laissez-faire. Hands off. Summers at 84 Warner Ave, she’d lock the door after lunch and say I’ll see you at five. What if I have to pee? Use your imagination. Use the woods. You were on your own, but you didn’t want to betray her trust. She had her limits. There was nothing so scary as trying to sneak in the house at three in the morning, tiptoeing across the kitchen, thinking you’d made it, and then look to the living room and see the cherry of her cigarette glowing in the dark and hear her say, “Sit down.” We ate the same meals on the same days for years. We ate early—4:30 or 5. Our table talk ran to imperatives and complaints: You’re not leaving the table until you’ve eaten every last bite of your supper; Stop playing with your food; My jaw hurts from chewing; I can’t let the vegetables touch the meat, and This spinach is making me sick. All the while Shep was under the table devouring our refuse. Dot may have left us largely to our own devises, but she did raise four kids who love one another and cherish the families we come from and are a part of.

Like her father before her, Dot did not trust doctors, not as far as her own physical or emotional health was concerned. She refused to answer questions or volunteer information. Her fears and her regrets were her own and were nobody’s business. She defied the world with what I think of as an insecurity blanket held close to her chest. You could see it, but she wouldn’t let you take it away. She may have been in need, may have felt weak, but to admit to vulnerability was intolerable. She told me that she had secrets that she never shared with anyone, not friends, not family. And she wasn’t starting with me. She loved a crisis, just not one of her own. She sprang into action when someone else was hurting. When a sibling needed a place to stay, Dot invited them into her home. Aunt Bea lived with us for a time, so did Uncle George, and Aunt Lou and her kids. The Dufresne family always got more interesting and lively and unpredictable when the Berards moved in, especially the Berards named Holland.

Unlike her husband and her siblings, Doris was not a storyteller. But on a road trip from Worcester to Tampa a couple of years ago, Doris, who was geographically challenged, and who said as we crossed the George Washington Bridge, “Is this Virginia or are we still in New York?” surprised me with some family revelations. She confessed that she regularly lied to her parents when her sister Bea, the wild one, snuck out the window to meet a date. She was here all night in bed with me, she told them. An aunt, I learned, was left at the altar, but later married the man with cold feet. Andy and Hector Berard, who married the sisters Bea and Agnes Lucier, claimed to be brothers, were thought to be cousins, but were not, in fact, related at all. Her sister Paulette died at birth. She and her friends got so rowdy in a New York hotel that the security guard was called to warn them about the noise. He stayed and partied with them for two hours. Three days of revelations on that trip, not the great revelation, to quote Virginia Woolf, that never came, but little illuminations, like matches struck unexpectedly in the dark. In Savannah, as Mom and I were walking back to the hotel from supper in the rain, she with her cane and slippery boots, me holding onto her arm with one hand and the umbrella with the other, a man passing us said, “Hello Teenagers!” and then a woman offered to sell me a palm rose for “your lady.”

Doris died with an unbeaten record in the Last Person Standing football pool, but not before selecting her remaining picks for the season. She did not go gentle into that good night. She raged against the dying of the light. But she was weary at the end and said so. She was ready. She was tired. When she lost the use of her legs in the final weeks, she told me if she were 60 she’d be angry, but she was not.

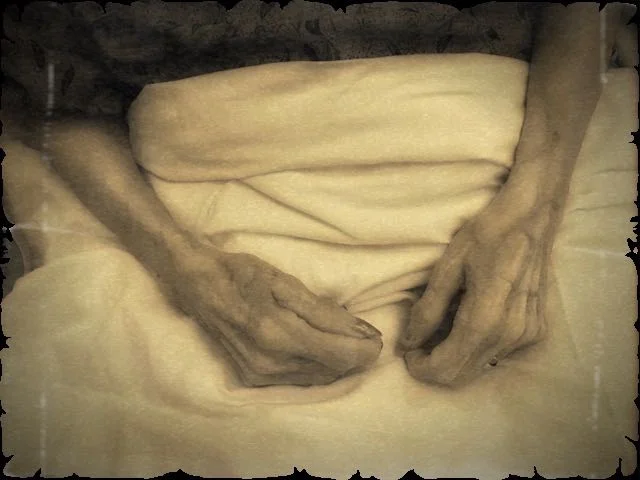

Memories are our waking dreams. They’re how we see the people who aren’t really here. We remember them and we tell their stories. That’s how we keep them with us, how we keep them alive, how we save them from oblivion, how we make meaning, make sense of the world and of our own lives. Stories and memories offer our only happy ending. My last memory of Mom is of her asleep in her hospice room. I looked at those arms that held me, those hands that rubbed my back and wiped away my tears, and in her hands she held a laminated prayer card of Lefty from Mercadante’s Funeral Home. Those hands. That marriage. Good night, Memere Dot. So long, Doris. Goodbye, Mom.